by Shari Biediger, San Antonio Report, August 18, 2021

Kayaks are stacked neatly beside the river, and a rope swing sways in the breeze. The Hopi, Blackfoot, and other cabins are quiet, their wooden bunk beds stripped of bedding. Campfire pits hold only ash.

As summer winds to a close, so does nearly a century of friendship bracelets and time-honored traditions, roasted s’mores and gut-busting skits, cooling swims, and carefree play at Camp Flaming Arrow.

The Hill Country sleep-away camp, owned and operated by the YMCA of Greater San Antonio since 1926, will be sold to reduce the nonprofit’s expenses and offset losses incurred during the pandemic. The listing agent said interest in the property was strong and a deal is expected to close this fall. But there’s no word yet on the buyer’s plans.

Placed on the market earlier this year, Camp Flaming Arrow hosted its last campers in July. A total of 800 kids attended throughout the summer, after the pandemic temporarily shuttered the camp in 2020.

After the children packed their bags and left the camp, counselors gathered around a bonfire to say their final farewells, singing traditional camp songs and sharing memories.

“No one didn’t cry,” said former camper-turned-counselor Kylie Helterbrand, one of thousands — no one can say exactly how many — who have spent their summers at the 213-acre campground in Hunt.

Tears flowing like the Guadalupe River have always marked the closing ceremonies of camp as kids say goodbye to long summer days spent with lifelong friends, Helterbrand said. But this year was especially mournful for both the kids and the counselors, as they looked back on what the camp had meant to them and so many others, and made their way one last time past a symbolic totem pole and over a river crossing, headed for home.

“It was like the first place where I felt truly loved by others who aren’t in my family and accepted by all,” Helterbrand said. “It is a judgment-free zone; you can be as weird as you want and you could be exactly who you are.”

YMCA officials have been planning for this day for several years, said Sandy Morander, president and CEO of the YMCA of Greater San Antonio.

“Resident camp has been on our list pre-COVID as an area that we were struggling with,” Morander said. “The new landscape in resident camping is very competitive — [there are] a lot of new facilities, and the business model for a resident camp to be a break-even proposition is based on volume.”

Throughout the Hill Country, new camps have sprung up or changed hands, creating more options and raising the bar in terms of amenities.

Likewise, land values are through the roof with demand for rural acreage and prices rising sharply in the last year, according to data from the Texas A&M Real Estate Center.

While the camp was a gift to the YMCA, Morander said running Camp Flaming Arrow costs a “couple million dollars” a year, and has operated at a $300,000 annual deficit for the last 10 years. In 2019, the YMCA reported to the Internal Revenue Service a total revenue of $38.1 million and total expenses of $38.2 million.

For a camp like Flaming Arrow to cover expenses, at least 300 campers per week in an eight- to 10-week summer are needed, Morander said. Flaming Arrow can accommodate about half that, and in recent years, about half of all campers attended with the help of financial assistance.

“That location, although it is beautiful, it is limited in terms of current capacity,” she said. “It just logistically was going to require anywhere from $12 million to $18 million in capital investment in order to bring that camp to the current standards.”

Even after such upgrades, there was no guarantee the camp could be sustainable, Morander said.

When the YMCA board of directors evaluated the number of children served through the camp versus the number of people who are served year-round through its programs and facilities, they determined the nonprofit’s resources should go to the greater number. Pre-pandemic, the YMCA had 70,000 members and another 125,000 program participants.

The board elected to also close the YMCA facility on Landa Street in New Braunfels and sold the building for $2 million in July. The Y’s administrative offices on Rhapsody Drive in North San Antonio also recently sold.

‘Hey, hey, CFA’

But Camp Flaming Arrow as a brand is not gone forever. Some day-camp programming will continue at the YMCA’s 1,200-acre Roberts Ranch in Comfort, which could one day offer a resident camping experience under the Flaming Arrow flag, Morander said.

“We’re preserving the name [and] we will incorporate it in our future work and preserve the opportunity to reinvent ourselves in Comfort,” she said.

That’s little comfort to the people whose fond memories of Camp Flaming Arrow have lasted into adulthood and want to see the camp continue. “We were all devastated,” Helterbrand said when they got the news last spring.

Real estate broker Charles Davidson of Republic Ranches said that when the property was first listed, he took at least one call a day and gave tours for prospective buyers up to three times a week.

A full tour on Davidson’s utility terrain vehicle takes several hours, as the property includes 2,112 feet of accessible frontage on the south fork of the Guadalupe River. Private homes line the opposite bank. Across the camp property, mature trees and wildlife are abundant in a natural landscape marked only by hiking trails that lead to an overlook with sweeping views of the camp and river valley.

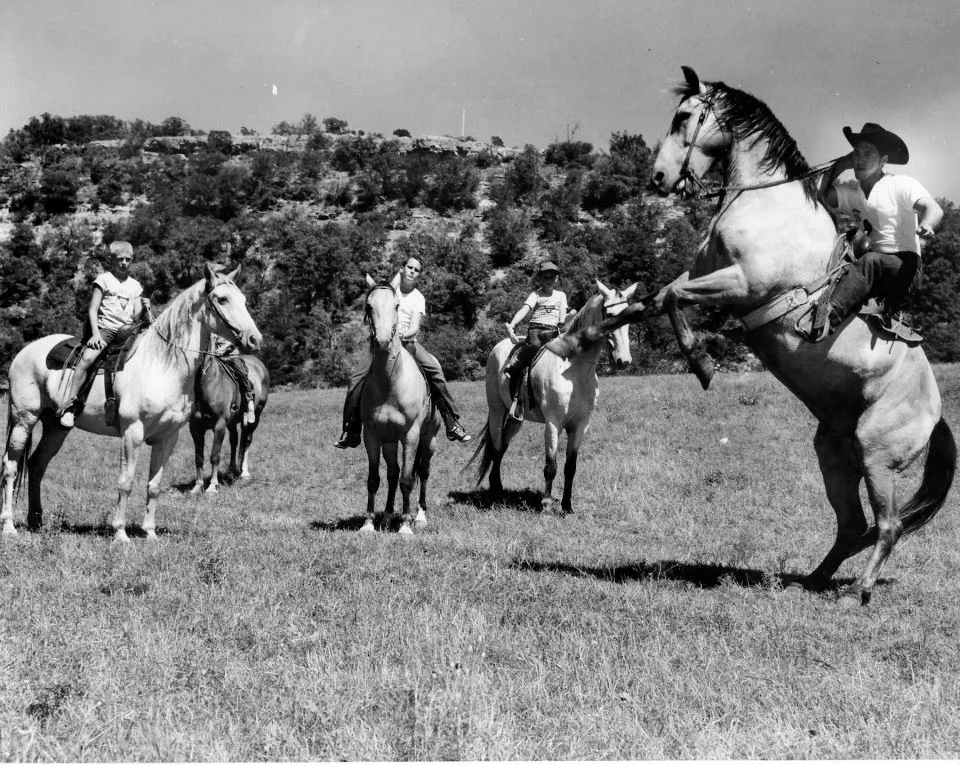

The camp has its own water well and a large in-ground swimming pool plus rustic cabins, staff homes, equestrian facilities, amphitheaters, a recreational building, sports fields, water slide, and docks. A suspension bridge spans a creek and leads to soccer fields and nylon hammocks clustered near a river shaded by Cypress.

Even with echoes of “hey, hey, CFA,” now hushed, the bucolic scene looks more like a pause than an end.

In the dining hall where painted stools are perched atop long tables, a chalkboard still has the final day’s menu: chicken pot pie, salad, banana pudding. Hand-painted rocks fill the flower beds around the craft cabin and at the pool a sign lists the campers, by cabin, who are swimming that day.

A camper named Emily joined others in memorializing her 2021 stay by chalking her name and a smiley face on a cabin’s porch beams. The hillside fort that campers built of fallen limbs still stands.

One last look

“Emotionally, they’d love to buy it,” Davidson said of all the former campers who have called him. “But they’re not ready to write the check.” The $6.45 million price tag is more than most individuals, or even groups of individuals, can manage.

Being the camp’s operations director for 13 years has been a “dream come true” job for MaryAshley McGibbon. She said she’ll miss witnessing the change in kids from their first day, when they are nervous and shy, to the last day of camp.

“They’re just in the middle of it and so alive,” she said. “You can’t tell the wealthy kids from the scholarship kids — they’re just kids. No electronics, nothing but [outdoors], bad air conditioning, and river water.”

These days, between packing up the camp, writing grant reports, and preparing to move out, McGibbon is taking calls from former campers who want one last look around. “If someone’s here, we make that happen,” she said.

Growing up, YMCA CEO Morander attended summer camp and credits her first leadership roles, jobs, and lasting friendships to the camp. “So I understand what resident camps mean in a family or in an individual’s life,” she said. “Camp Flaming Arrow has served us all very well — those memories will never be taken away.

“I have told anyone who has asked, if we didn’t get calls and upset people, we didn’t do a very good job for the last 100 years. If no one was going to miss it, then certainly we did something wrong.”